|

Carrier and Horseman:

On fibs and fakes in early writings

False statements are sometimes passed down in the literature about

pigeons over the centuries until today and are taken as truths.

Often mistaken. Sometimes also consciously in order to increase the

reputation of one's own breed or to exaggerate one's own

achievements or those of breeders in the region. Moore’s story on

the Carrier and the Horseman is an early example.

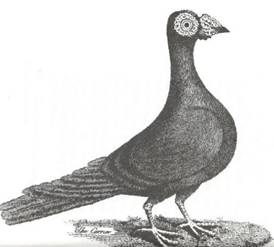

The carrier at WILLUGHBY and the show carrier at Moore

It is clear not only from its flight ability but also from its

phenotype that the English carrier that Moore praised as the king

of pigeons in 1735 was not the carrier of the Turkish Empire

described by Willughby in 1676/78. The messenger pigeon of the

Turkish Empire was the size of an ordinary pigeon or slightly

smaller. According to him, Moore's carrier is larger than most

breeds. At 20 ounces (approx. 567 g), almost twice the weight.

Length from tip of beak to end of tail 15 inches (38.1 cm) instead

of 34-35 cm (pp. 25ff.). The beak length of the racing homers is

moderate (about 23 mm from the tip of the beak to the angle of the

beak), while the English Carrier is 38 mm according to Moore,

probably from the tip to the eye. So about 30 mm from the tip to the

corner of the mouth. Eye edges and beak wart are more developed in

the Carrier described by Willughby than in the common pigeon,

extremely pronounced in Moore's description. The figure of the

carrier at Willughby is not in line with the description in the

text. The use of such an illustration rather highlights the problems

that authors at the time had with appropriate illustrations for

their texts. John Gray, who published Willughby’s work posthumously,

reported on these problems in detail in the introduction. But even

if the messenger pigeon would have looked more like the Turkish

pigeons depicted by Frisch in 1763 and by Neumeister in 1837, the

question remains as to how such pigeons would turn out to be that

size, weight, beak, face, neck and leg length in 50-60 years. Such

modified pigeons as in the Treatise 1765 certainly could not be

derived at by through pure breeding, even if this impression seems

to be intended by Moore.

Turkish Pigeon at Frisch 1763 and Neumeister 1837

Carrier in the Treatise 1765 and at Tegetmeier 1868

Suggestions from Moore

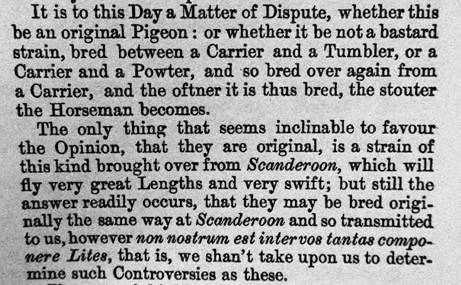

With his sudden, rapid transition from the describing his carrier as

the king of the pigeons to depicting the achievements of messenger

pigeons in antiquity (p. 28), Moore gives the impression that

precisely this pigeon is the legitimate descendant of the ancient

messenger pigeon. Only he is entitled to the name 'Carrier' and its

legend. Thanks to high breeding, he would be now only too valuable

for the messenger service. He himself indirectly admits that his

story is not valid when he struggles to make a clear statement about

the Horseman. This is what he calls the messenger pigeon preferred

in England at the time (p. 31). He pretends not to know whether it

was a separate breed or a crossbreed, "we shan't take upon us to

determine such Controversies as these" (p. 31). Not rhetorically

clumsy, because both given answers were bound to mislead the

reader. As an experienced pigeon fancier, he would have known that

both were wrong. It was not a new breed nor was it a crossbreed. The

pigeons were obviously the messenger pigeons still used in the

Turkish Empire at the time, which Willughby had called 'carriers'

and Moore renamed ‘Horseman’. He indirectly admits this. Because he

reports that the same kind with the same abilities came to England

from Scanderoon (ibid). His realization should have been that there

were still the same carriers in Scanderoon as in Willughby’s time.

By renaming the original carrier to Horseman, the fib of his Carrier

as the ancient messenger pigeon was successfully covered up.

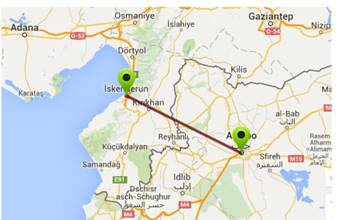

The carrier from Scanderoon

Scanderoon, temporarily Alexandretta and now Iskenderun, is the port

from which English merchants from Aleppo maintained a pigeon post to

be informed of incoming ships. Henry Teonge reported about this in

his ship's diary 1675-1679. As a ship's chaplain, he accompanied

trips of the Royal NAVI from London to the Levant and also to

Scanderoon. The pigeons would cover the distance of about 60 miles

in less than three hours. It is obvious to assume that these pigeons

were Willughby’s carriers, which could be seen in the royal aviaries

in St. James's Park.

The image of a 'Scanderoon' or 'Horseman' by Peter Paillou in 1745

has only recently become accessible. Hand-signed on the back with

Scanderoon, recorded in the accompanying text as Horseman. Almost

too beautiful not to be fake! A homer pigeon type with longer legs

and strong upper beak warts, as shown by old racing pigeons in some

tribes. Scanderoon and Horseman are probably rightly equated in the

accompanying text.

Scanderoon by Peter Paillou (England c. 1720 - c. 1790), 1745.

Historical flight route of messenger pigeons between the port of

Scanderoon (Iskenderun) and Aleppo

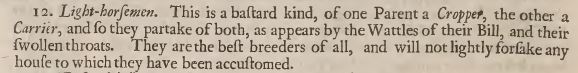

Willughby does not mention either name among his races. If the

carriers in the royal aviaries also came from Scanderoon, which is

likely, then they are of the same origin and race. In Willughby,

however, the term horseman can be found in the light horseman, which

is described as a cross between carrier (=horseman) and cropper. The

name is probably a reference to light cavalry (light horse

regiments) because of their agility. In French literature he appears

as Cavalier for identical or similar pairings.

Speculations about the change from a Scanderoon to a show carrier

Lyell gave a possible explanation for the change in the breed during

Moore's time in 1881. In Calcutta in India, he found pigeons that

did not differ from the English Carrier of his time and originally

came from Baghdad. Imports of such animals could have displaced or

improved the popularity of the previously rather inconspicuous

carriers in England around 1700. A new breed for which a

promotional name and legend were sought. Moore could have knitted

these.

Brent mentions a second possibility (3rd edition 1871, p. 24).

Crossing existing warty pigeons (such as the Turkish pigeon by

Neumeister, the Carrier or 'Scanderoon' described by Willughby, or

Barbary pigeons by Manetti) with large-format bagdettes that existed

on the nearby continent. Van Vollenhoven from Utrecht dedicated a

few verses to the Bagdette in his verse-form work in 1686. Although

there is no strong wart on the beak, there are more developed

circles around the eyes. The thighs are barely feathered, they are

short and round in the body and 'steady on their feet'. The neck

resembles that of a swan. Jakobus Victors drew such an animal in

1672. There is much to suggest that Brent’s version is correct.

Carrier and French Bagdette ash red bar at a German Pigeon Show.

The similarity in the appearance shows that the name at Neumeister/Prütz

1876 as English straight-beaked bagdette is justified. Source:

Sell, Taubenrassen 2009.

The combination of warty pigeon and bagdette figure is a breeding

achievement that deserves recognition. The result, however, is a

cross product, instead of one with a long pedigree of pure royal

blood. And therefore, not the 'ancient messenger pigeon of the Near

East and North Africa', which the German BDRG standard still calls

it today.

Literature:

Brent, B.P., The Pigeon Book. Containing the Description and

Classification of all the known Varieties of the Domestic Pigeon

London (3rd ed. 1871)

Frisch, Johann Leonhard, Vorstellung der Vögel in Deutschlands und

beyläuffig auch einiger fremden, mit ihren Farben…Die Zehnte

Klasse, die Arten der Wilden, Fremden und Zahmen oder Gemeinen

Tauben, Berlin 1763.

Lyell, J.C., Fancy Pigeons, London 1881, 3rd ed. London

1887.

Moore, J.,

Pigeon-House. Being an Introduction to Natural History of Tame

Pigeons. Columbarium: or the pigeon house, Printed for J. Wilford,

London 1735.

Sell, A., Taubenzucht. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen züchterischer

Gestaltung 2019.

Sell, A., Critical Issues in Pigeon Breeding, Achim 2023, pp. 37-42.

https://www.taubensell.de/011_Neu_Archiv/standards_von_rassetauben.htm

Tegetmeier, W.B., Pigeons: their structure, varieties, habits

and management, London 1868.

Teonge, Henry, The Diary of Henry Teonge. Chaplain on Board H.M.’s

Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak 1675-1679, edited by Sir E.

Denison Ross and Eileen Power in the Broadway Travellers. First

published in this Series 1927.

Willughby, Francis,

The Ornithology in Three Books. Translated into English, and

enlarged with many Additions throughout the whole work by John Ray,

Fellow of the Royal Society, London 1678.

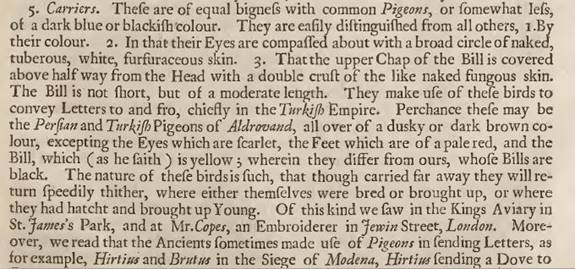

Annex: Excerpts from Willughby 1678 and Moore 1735

Willughby 1678

Moore on the Horseman and Scanderoon, Moore 1735, p. 31.

|