|

Identity theft: carriers

and carrier pigeons

The enthusiasm for pigeons

with oversized beak and eye wattles is not so much in active

fanciers of racing homers, but in fanciers of 'beauty homers'. In

many cases, these really do hold them for the original messenger

pigeons, although there was never a messenger pigeon with such large

wattles as some of the beauty homers today.

The strain of racing homers,

with which the author in his youth competed at the first races,

still based on chicken feed, also tended to stronger nose wattles

(Fig. 1). However, these were never dimensioned as they are today

sought by some so called beauty homers with reference to the alleged

ancient tradition as carrier pigeons.

Fig. 1: Racing homers in the

author’s loft 1957

If one sticks to the facts,

then neither the Belgian racing homer, which essentially goes back

to high-flyers and rough owls, nor the "Turkish pigeon" as

historical messenger pigeon (carrier) of the Orient possessed an

excessive wattling. The reference to the old messenger pigeons may

be promotional for some exhibition breeds, however, it is not

correct as justification for extreme wattles. Gessner (1555 and

1557) and Aldrovandi (1600, 1610) still do not mention messengers or

wattle pigeons in their descriptions of breeds. Only in the enlarged

version of the ‘Gessner’ by Horst (1669, p. 178) are they mentioned

in the German-speaking world as 'Dückmäuler' (thick moulth) from

Frankfurt. On the upper beak they would have a 'warty proliferation'

and warts around their eyes. Both would increase with age. They are

difficult to get used to, and it is the say, "that they fly back

from 40 miles to their proper place and are therefore often served

in sieges of theirs as messenger or letter carrier." At about the

same time, 'carriers' were described as carrier pigeons in the

Turkish Empire by Willughby 1678 similarly: size of the ordinary

pigeon, the beak of moderate length, the eye framed by bare skin and

on the beak a double crust like skin (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Description of the

carrier pigeon (Willughby 1678)

The description was made not

only by hearsay, because such pigeons would have been seen in the

Royal Aviary in St. Jame's Park and at another point in London. No

indication in both sources on an extreme wattling, which also covers

the lower beak. Willughby also mentioned 'Barbary Pigeons', which

run in Germany as ‘Indianer’. The beak is short and thick as in the

owls (turbits), the eye cere as the carrier. The eye color is white,

but there were also reports of red eyes. Drawings of the Turkish

Pigeon can be found at Frisch 1763 and Neumeister 1837 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Turkish Pigeon at Frisch 1763 and

Neumeister 1837

Pigeons with very strong

wattling, appeared only in the first monograph on domestic pigeons

by the London pharmacist Moore (1735) in the description of his

carrier. The wattling at the upper beak would be accompanied in this

sometimes by two excrescences on each side of the lower beak. In his

time was already bred on beauty attributes to a standard. His

carrier was much larger than the ordinary pigeon, the beak long,

straight and thick, the neck long and thin. Pictured is the ideal in

1765 in the Treatise. Impressive also the picture at Tegetmeier 1868

(Fig. 4). Little resemblance to the description of the original

carrier at Willughby and with the early pictures of the Turkish

Pigeon! Brent (1871) probably rightly suspects that the changes in

the neck and beak length were due to early crossings with French

bagdettes.

Fig. 4: Carrier in der Treatise 1765 und bei

Tegetmeier 1868

The increase in the wattling

may have been achieved by selective breeding and the use of

mutations in the desired direction. Overall, an impressive breeding

performance: For Moore and his friends, the English carrier was the

king of pigeons on the account of beauty and great sagacity. To

prove sagacity an impressive legend was needed. Moore created that

by transferring the history of the old 'carriers' of the Orient to

his now significantly changed exhibition carrier. Identity theft we

would call it today. Besides Tegetmeier, other early authors, such

as Selby (1843) and Fulton (1878), pointed out that his carrier had

already moved far from a messenger pigeon. To quote Tegetmeier: The

name carrier was regrettable, since one could not attend a show

without anyone who was deceived by the name speaking of them as the

true messenger pigeons (Tegetmeier 1868, p. 44). That does not deny

the attractiveness. Even Darwin (1868 Chapter VI) mentioned “the

Carrier with its wonderfully elongated beak and great wattles, the

Barb with its short broad beak and eye-wattles” that were developed,

however, from predecessors with beaks and wattle incomparably less

developed (ibid).

As an exhibition pigeon, the

carrier conquered the world starting from England. Also the heavily-wattled

short beaked English 'Barbs' became a figurehead of English breeding

art and were to be found as ‘Indianer’ of the English type in

Germany at the exhibitions until the 1960s.

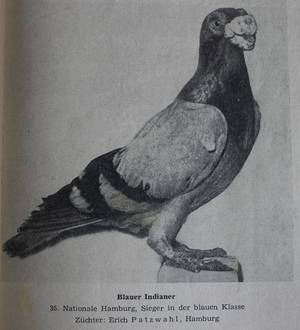

Fig. 5: Barbary Pigeon of

the old type in Germany, champion at the German National Hamburg

1953 (Taubenwelt 2/1954).

An example of an English

carrier before 1900 is preserved in the Natural History Museum in

Braunschweig. Labeled is it as 'bagdette'. This is because the

English carrier in Germany was also called 'Long Beaked Bagdette'

(in contrast to the Nuremberg Bagdette). It was donated in 1887 by

Hugo du Roi, then president of the Club of German and

Austrian-Hungarian Poultry Breeders.

Fig. 6: Photo in the

description of the Italian Exhibition Homer

(Viaggiatore Italiano da esposizione)

http://www.agraria.org/colombi/viaggiatoreitaliano.htm and a

preparatory of an English Carrier from 1887 at the Natural Historic

Museum Braunschweig

With the English carrier,

the myth of the English carrier spun by Moore as an ancient

messenger pigeon was evidently transferred to other countries and

the heads of admires. That should be the background for the

presentation of similar pigeons as old Polish and old Hungarian

pigeons as well as Italian beauty pigeons. Rather embarrassing that

one can still read in the German standard, that the English carrier

was an ancient messenger pigeon of the Near East and North Africa. A

sustainable marketing of Moore, which also today's marketing experts

will have to concede!

It is an open question

whether the wrong statement of the English carrier's past as a

carrier pigeon today is positive for the breed. Probably one would

perceive the features of the English carrier in terms of neck and

leg length, the sloping stand and the peculiarities in head shape

and beak even better, if there were not the permanent comparison

with the homing pigeon in the background.

Fig. 7: Young Carriers with

restriction of beak wattle at the upper chap of the bill and a fully

developed adult at the right

Wattle pigeons have had

followers for about three hundred years now, and will continue to

have them, even without the mistaken claim of a past as a messenger

pigeon. Thus, we should accept that many of the pigeons today

propagated nationally and regionally as old messenger breeds are in

the tradition of the exhibition carrier and early forms of the

English Barbary Pigeon and not in that of true homing pigeons.

Literature:

Anonymous,

A Treatise on Domestic Pigeons, London MDCCLXV (1765), Reprint

Chicheley, Buckinghamshire 1972.

Brent, B.P., The Pigeon Book. Containing the

Description and Classification of all the known Varieties of the

Domestic Pigeon, with numerous highly-finished Illustrations, third

edition London (1871).

Darwin, Charles, The Variation of Animals and

Plants under Domestication, Vol. I,

London, John Murray 1868.

Fulton, R., The Illustrated

Book of Pigeons. London, Paris, New York and Melbourne 1876.

Gesner, Conrad, Vogelbuch, Frankfurt am Main

1669, aus dem Lateinischen mit Verbesserungen durch Georgium

Horstium, Reprint Schlütersche Verlagsanstalt und Druckerei

Hannover 1995.

Moore, John, Columbarium: or

the Pigeon House, London 1735.

Neumeister, G., Das Ganze der Taubenzucht,

Weimar 1837.

Selby, P.J., The

Naturalist’s Library, edited by Sir W. Jardine, Bart., Vol. XIX.

Ornithology. Pigeons, Edinburgh 1843, (preface 1835).

Sell, Axel, Brieftauben und ihre Verwandten,

Achim 2014.

Sell, Axel, Pigeon Genetics.

Applied Genetics in the Domestic Pigeon, Achim 2012.

Sell, Axel, Taubenrassen. Entstehung, Herkunft,

Verwandtschaften. Faszination Tauben durch die

Jahrhunderte, Achim 2009.

Tegetmeier, W.B., Pigeons:

their structure, varieties, habits and management, London 1868.

Willughby, Francis,

Ornithologia, Libres Tres, Londini MDCLXXVI (1676);

The Ornithology in Three Books. Translated into English, and

enlarged with many Additions throughout the whole work by John Ray,

Fellow of the Royal Society, London 1678.

|