|

Isabell in pigeons and breeding success with guided mate choice

Isabella in old literature

Isabell coloured pigeons are already mentioned in old literature as

a speciality. Neumeister mentions them in pouter pigeons in 1837.

Coloured drawings promoting the colour scheme are first found in

pigeon books in England. Thus, in Tegetmeier 1868 a muffed pair. The

coloured drawing in Fulton 1876 is clearly recognisable as a pouter

pigeon. The delicate colour of the Isabella is emphasised by the

adjacent red and yellow in comparison.

Fig. 1: Isabella pigeons at Tegetmeier 1868 and Fulton 1876

The muffed Isabella Pigeons are named differently in old literature,

sometimes as Dutch, sometimes as Saxon Pouters.

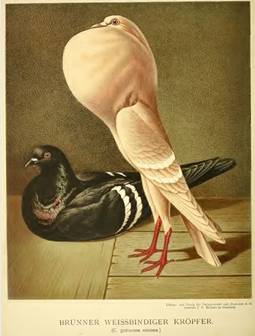

Prütz 1885 shows a clean-legged Brunner Pouter. Behind it in the

drawing a black with white bars. Isabella are often shown in

drawings together with other white-barred ones, as in Fulton's work.

However, the colourations and white bars are genetically based on

different hereditary factors. The fact that they were often shown

together in the picture did not make it easier for the breeders and

later also not for the decoding of the genetic structure.

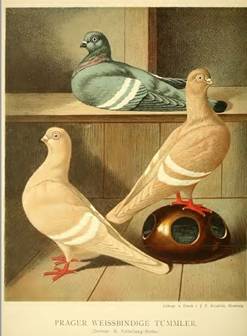

Fig. 2: Isabell-coloured Brunner Pouter and isabell-coloured Prague

Tumbler at Prütz 1885. In the background a light blue with white

bars.

In Prütz's work, next to the Prague isabell-coloured Tumbler, a

light blue with white bars, which is not quite realistic.

Genetically, like the Isabella, it has the hereditary factor

Dominant Opal (Sell 2012, 149-155). The tail bar of the light blue

in reality is bleached to a lighter whitish colour, different from

the drawing.

Breeding problems with Isabella

Despite all the praise, there have always been only a few breeders

of Isabella. This may also be due to ignorance of how to breed this

colouring best. Until the 1960s, however, the breeders did not

mention any breeding problems with Isabella and also not of light

blues with white bars, checks or lacing, which are linked to them by

the common hereditary factor Dominant Opal. Then there were reports

from breeders about poor breeding results. They suspected inbreeding

or diseases as the cause. In the genetics group around W.F.

Hollander in the USA there were notes in the 'Pigeon Genetics

Newsletter' published by him around that time that it was difficult

to obtain purebred Dominant Opals. And if you had an animal that

could be homozygous, there would be vitality problems.

Andreas Leiß from Vienna succeeded in breeding such purebreds in

feral pigeons. He documented them in photos and also showed the

problems of the surviving pure-bred Dominant Opal. Whitish/grey in

colour, not attractive and vitality problems. The reared female died

after a short time, the juvenile cock lived a little longer but did

not reproduce. This matched other reports of grey/white juveniles

already dying in the nest.

Investigation into the reproduction of isabella

It is the merit of Wolfgang Schreiber and his breeding friends of

the Brno and Saxon Croppers to have investigated the thesis of the

failure of the pure dominant opal on a broad data basis. The results

confirmed the earlier assumptions on the lethal or semi-lethal

effect of homozygosity for Dominant Opal (Schreiber 2004). It was

found that from pairs of two isabell-coloured pigeons (648 eggs) on

average 3.2 young were born, from mixed pairs (665 eggs) 5.2. This

could be broken down into a lower number of eggs laid per pair and

lower fertilisation rates in pairs formed by two isabella, lower

hatching rates from the fertilised eggs and higher mortality rates

after hatching before banding (see also Sell 2012).

From Punnett's squares one can read that half of Isabell x Yellow

are expected to be isabell-coloured. That is 2.6 isabella per pair

from 5.2 kittens. From Isabell x Isabell with 3.2 kittens there are

arithmetically just under 2.2 isabella per pair. In percentage terms

it is more, but in absolute terms it is less than in the comparison

pairing.

Fig. 3: Brunner Pouter yellow (complementary color to isabell.

Brunner Pouter isabell (Günter Dietze) and Saxon Pouter isabell

(Dieter Geisemeyer).

Source: Sell, Pigeon Genetics, 2012, photos: Layne Gardner

Instead of yellows, one can also mate with reds as a complementary

colour, if possibly the colouration is also somewhat darker. Spotted

bills are sometimes mentioned as a disadvantage. Epistatically

masked, the reds and yellows should genetically possess the bar

pattern.

Change in the proportion of isabella in the stock without selection

in the case of random mate choice

Lethal genes are quickly lost in nature. This would also happen to a

strain of isabella or light blue pigeons left to itself. If the

breeding stock for the next breeding period is completely replaced

by the offspring, this can be made plausible in fast motion by

simple model considerations. Let's start with a flock of pairs

Isabell x non-Isabell (100% heterozygous Dominant Opal). Directly

readable in Punnett's square, a quarter of the kittens do not have

the factor. Half of the kittens are heterozygous Dominant Opal like

their parents. A quarter of the kittens are homozygous Dominant

Opal. These die already in the egg or shortly after hatching. With

random selection from the young of the year for further breeding,

the percentage of Dominant Opal will have dropped from 100% of the

stock to 66.6%.

When these offspring mate with each other, three combinations are

conceivable. Non-carriers of Dominant Opal with each other (1/9 of

matings), mixed carriers of the gene with each other (4/9 of matings)

and a carrier of the gene with a non-carrier (4/9). Failure by

purebred Dominant Opal will occur in these matings when two trait

carriers mate with each other. If the reproductive behaviour is not

influenced by other confounding factors, the proportion of

reproductive Dominant Opals will be reduced to 50% in this cohort.

If one follows the model's calculation instruction over the

generations, the proportion thins out further to 40%, 33.3%, 29%,

etc. (cf. Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Model observation of the percentage of heterozygous Dominant

Opals with random mate selection over the generations. Exchange of

parents by offspring after each breeding year.

Stable ratio of 50% of heterozygous individuals in the wild

White-throated Sparrow due to sexual preference for differently

coloured mates (negative disassorting mating)

It is interesting to look for parallels with other animal species.

Frank Mosca recently pointed to studies in the American

White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis). Here, too, there is

a dominant inheritance of the colour variant 'white' over 'tan', the

other variant. By 'white' is meant that the throat patch and a line

above the eye and over the head appear white and not brownish (tan)

(cf. Fig. 5). Here, too, the gene that is considered dominant seems

to reduce vitality in the case of pure heredity, according to the

observations. Why do they still exist, and stable in the population

by 50%?

Fig. 5: White-throated Sparrow, the 'White' variety with white

instead of brown (tan) markings. Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wei%C3%9Fkehlammer#/media/Datei:Zonotrichia_albicollis_CT1.jpg

According to observations on mate choice, mating of white x tan and

vice versa occurred almost exclusively in free-living populations.

As recommended for Dominant Opal in pigeons: Isabell x Yellow and

vice versa. The other matings occurred in the 1 percent range. These

few pairings probably triggered by the absence of other partners. As

with species crosses between domestic and wild pigeons or doves,

there provoked by the keeper. Pure-bred 'whites' were therefore

hardly found in nature, 3 out of 1,989 birds, one male and two

females. The male remained smaller than normal (Hedrick, Tuttle,

Gonser 2018).

In feral domestic pigeons, Johnston and Johnson (1989) had reported

preferences for certain and also different from the own colourations

in mate choice (negative assortative mating), but nowhere near as

clearly as in the White-throated Sparrow. The molecular genetic

difference between Tan and White was found to be chromosomal

inversions involving about 1000 genes on the white-chromosome, with

genes affecting not only colouration but also other characteristics

such as behaviour (ibid.). Thus, whites and tans are differently

aggressive, they also differ in brood care. Among the genes in this

area, presumably also those that directly or indirectly influence

mate choice.

Reactions to lethal genes in pigeon breeding

According to the breeding recommendations for pigeons, in the case

of genes with lethal or semi-lethal effects, two trait carriers

should not be mated with each other, also from the point of view of

animal welfare. The reasons can be seen from the above. In nature,

in some cases, negative assortative mate choice ensures that the

heterogeneity of the initial stock is maintained over the

generations. In pigeon breeding this is simulated by guided matings.

The question of whether there is a natural affinity for divergent

coloured mates in dominant opal-coloured pigeons - similar to the

White-Throated Sparrow - does not seem to have been asked yet.

Whether preferences are signalled by colouration or by other

associated traits remains to be seen. Whether it is better to speak

of recessive or dominant can also be left open for Dominant Opal.

Historically, dominance is spoken of on the basis of colouration. If

the mortality of the young is put in the foreground, the effect is

recessive.

Literature:

Hedrick, Ph. W., Elaina M. Tuttle, and Rusty A. Gonser,

Negative-Assortative Mating in the White-Throated Sparrow.

Journal of Heredity, 2018, 223–231.

Hollander, W.F. (Hrsg.), Pigeon Genetics Newsletter, Volume 1962.

Johnston RF, Johnson SG. 1989. Nonrandom mating in feral pigeons.

Condor.

91:23–29.

Schreiber, Wolfgang, Erhebung über die Nachzucht isabeller Brünner.

Brünner aktuell 2004, 49.

Sell, Axel, Pigeon Genetics. Applied Genetics in the Domestic

Pigeon, Achim 2012.

|