|

Pitfalls in traditional and molecular genetic classification of

pigeon breeds

Pigeon breeds can be viewed and subdivided from different

perspectives.

1. historically, striking characteristics and behaviours are

described side by side when depicting domestic pigeons. In

Frisch 1763 and in

other early writings, these got designations for groups of pigeon

breeds such as pouters, tumblers, high-flyers, drummers etc., which

still differed from each other in other details within the group.

These groupings can still be found today as a classification scheme

in the book of standards of the pigeon fancier organisations.

2. the interest of Darwin

(1868) in this context was not directed towards the differences of

breeds and breed groups, but towards the succession of preliminary

stages and preliminary final stages of the development of breeds.

This enabled him to illustrate the rapid change of characteristics

under the influence of selection.

3. even before Mendel

(1865), but increasingly after him, breeds with other

characteristics were seen as a possible source for the improvement

of breeds or for the creation of new breeds by uniting positive

characteristics.

4. molecular genetic classifications of breeds in clusters are made

according to genetic similarities identified by DNA analyses. Breeds

with particularly high similarity to each other, but with a clear

distance to other groups, are grouped together.

Some statements about these studies give the impression that there

is little information about the relationships between breeds,

especially with pigeons:

„as

unlike with many other domestic species, few reliable records exist

about the origins of, and relationships between, each of the breeds”

(Pacheco et al., S.

137).

As explained below, this underestimates the wealth of information

available in the fancier literature. On the other hand, the

possibilities of making unambiguous statements are overestimated in

view of the breeding activities and multiple crossbreeding between

breed groups in the past.

Traditional classifications of breeds according to their utility,

appearance and behaviour

In the historical European literature on pigeons, the description of

characteristics of breeds and their presumed regional origin are

central. So, in Gessner

1555/1557 and in the revised version 1669, in

Aldrovandi around

1600, Willughby 1676,

Moore 1735 and

Frisch 1763.

Frisch had already

distinguished nine basic types and presented one example for each

group pictorially. Field pigeons and Montauben (month pigeons) as

ancestors of today's colour pigeons, drummer pigeons, pouters, owls,

tumblers, Turkish pigeons as representatives of warty pigeons,

Jacobins and fantail pigeons as representatives of the structural

pigeons.

Fig. 1: Representatives of two main groups of

domestic pigeons by Frisch

1763, Pouters and Turkish Pigeon (Source:

Sell: Taubenrassen

2009).

In the German book of standards the groups 'form pigeons’ and 'hen

pigeons' have been added. The heterogeneous group 'form pigeons'

also includes the large utility pigeons listed as a group in

Buffon 1772, among

them the giant pigeons already classified as 'Runts' in

Willughby 1676 and as

Romans in Dürigen

1886. In 2022, the breeding stock of the German BDRG shows 35 pouter

breeds from the 'prototype' shown by

Frisch, and far more

than 100 breeds of tumblers and high-flyers. The classification of

the NPA, the American Pigeon Breeders Association, is similar and

follows the tradition of other associations.

Historical classifications may be overtaken by development and prove

inaccurate.

Dixon

had already written this in 1851 for some subgroups of tumblers that

had degenerated from a flying point of view: they would be called

tumblers because they would roll over if they could still fly (p.

118). Associations sometimes react to changes that cannot be

overlooked by regrouping. For example, the Coburg Larks and Lynx

Pigeons, which were classified as coloured pigeons by

Dürigen in 1886, have

become form pigeons in the current book of standards, and Strasser

as former hen pigeons have also become form pigeons.

Darwin: Changes and emergence of breeds by selection

For Darwin, pigeon

breeds were important because he was able to use them as examples to

show the rapid change of characteristics through selection. It is

about the ancestors of these breeds and about the preforms that

still existed at his time. It is not the side by side of breed

groups that is of interest, but in this context the differences

between the breeds and their predecessors (parent stock). These are

indicated in his illustrations in dotted lines. He was able to show

the extreme change of characteristics in a relatively short time. In

the 'family tree' of the English Short Faced Tumbler, for example,

it is shown with a small figure and extremely short beak as the end

of a developmental path. Among its direct ancestors are the Common

Tumbler, common in England, and, more distantly, the related Lotan

Tumbler and the Persian Tumbler.

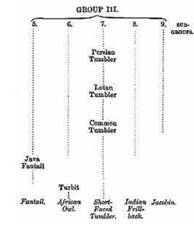

Fig. 2: English Short Faced Tumbler and its line of

development in Darwin

1868 (Source: Sell,

Taubenrassen 2009).

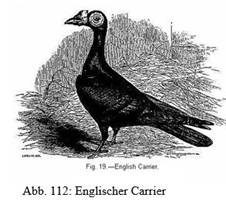

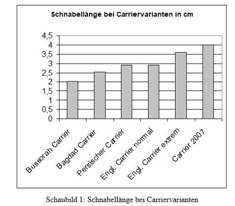

The Carrier, with a long beak and relatively high and slender

stance, is also at the end of an evolutionary line. Darwin had

measured 3.6 cm beak length from the tip to the corner of the mouth

in extreme specimens. The Dragon (now Dragoon), the Bussorah Carrier

and other Carrier breeds with much shorter beaks are mentioned as

predecessors in Darwin’s

illustration (cf. Sell,

2009, p. 124).

Fig. 3: English Carrier in

Darwin 1868, and

development of beak length over time (Source:

Sell, Taubenrassen

2009).

Whether the development of the beak length in both breeds was due to

selection alone remains to be seen. For in the historical literature

there are indications and evidence that the present French Bagdette,

which existed under other names at that time, was involved in the

development of the English Show Carrier, and, in the case of the

beak length of the English Short Faced Tumbler, also owls.

Aldrovandi

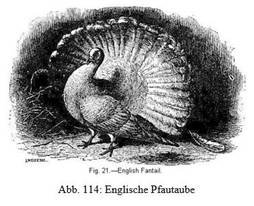

in Europe did not know the fantail in 1600. In 1669 it appears in

the version of Gessners

revised by Horst as

Cprian peacock tail. It was fetched from Holland by local noble

lovers for a lot of money. The number of tail feathers is given as

26 instead of the 12 of a normal domestic pigeon. This is also the

number quoted by Darwin with reference to

Willughby (1676).

Moore (1735) names 38,

Buffon (1772) 32 and

Boitard and

Corbié (1824) 42. In

England, according to Darwin,

it was not so much a question of the number, but also of the general

posture (general carriage). Today, this has changed even further

with extremely short backs (Fig. 4).

Willughby

(1676) describes them with at least 26 tail feathers instead of the

normal 12, Moore

(1735) with 38 and Buffon

(1772) with 32.

Darwin

quotes Boitard and

Corbiè (1824) who

counted 42. In England, however, it was not so much about the

number, but also about the general posture (general carriage). This

has changed even further today with extremely short backs according

to

Darwin

(Fig. 4, 10).

Fig. 4: Fantail at

Darwin

and development from Buffon

(1772) via P.J. SELBY

(1835/1843) to today on the cover of the book Taubenrassen.

Creation of new breeds and transmission of traits across breed

groups

The fact that traits - positive and negative - are hereditary was a

firm knowledge of practical animal breeding even before

Mendel. Under the

keyword "Livestock Breeding" in the Book of Inventions, Leipzig and

Berlin 1864, we find the following statements:

"In relation to performance ... the individual species, horse, goat,

cattle, etc., are not only, but also individual branches of these

species among themselves again very different. The name breed means

as much as a variety distinguished by special characteristics common

to all members of the breed. We only find breeds among those animals

which man has taken into his immediate environment, made into

domestic animals and accustomed to his service"... "But it is just

as certain ... that man has it in his power to form new breeds

according to his will"... (in German language, p. 204ff.). And

further on breeding strategies: "The animal breeder can now preserve

the existing breeds or change them in a refining way. A breed is

preserved by mating the best animals within it; it is improved by

inheriting forms or characteristics which it lacks for a desired

purpose or in general, namely by mating animals of different breeds

in which those desired characteristics appear sporadically" (Buch

der Erfindungen 1864, p. 204, quoted at

Sell, Taubenrassen, p.

191).

For many pigeon breeds this is documented in detail by

Boitard and

Corbié already in

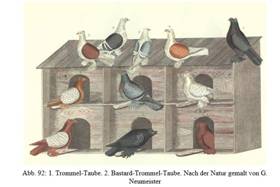

1824. In Germany, originally inconspicuous drumming pigeons were

adapted to the taste of the breeders by crossing with colour

pigeons. Thus, the newly developed drumming pigeon breeds were long

referred to in the literature as 'bastard drumming pigeons' (Neumeister

1837 and Neumeister /

Prütz 1876).

Fig. 5: Drumming pigeons and bastard drumming pigeons in

Neumeister 1837,

Neumeister /Prütz

1876.

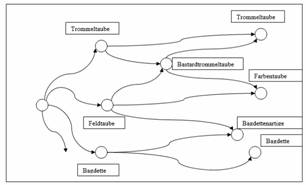

Sketch of the interrelationships of breed groups

(Source: Sell,

Taubenrassen 2009).

The group of tumblers and high fliers is particularly receptive to

traits originally associated with other breed groups. High stance,

long necks and long beaks due to influence of French Bagdettes (Fig.

6), short and thick beaks due to Owls, feather ornaments of Drummers

and Fantails, colourings of Colour Pigeons.

Fig. 6: German Magpie Tumblers in

Schachzabel 1910,

Magpie Tumbler in Lyell

1887 and English Magpie Tumbler from 1938, illustrated in

Levi 1969 (Source:

Sell, Pigeon Genetics

2012).

In Magpie Tumblers, pigeons modified by crossbreeding first appeared

as a 'modern type of the breed' before they became accepted as

successors to the old breed. This was also the case with Maltese

Pigeons, Kassel Tumblers and others (Sell,

2009).

Fig. 7: Maltese of old and ‘modern type’ at

Dürigen 1868 and 1906,

source: Sell,

Taubenrassen 2009.

Strasser and Lynx pigeons have also not developed from the pigeons

shown in Lavalle und

Lietze 1905 by

selection in figure and size alone.

Fig. 8: Change of the Lynx Pigeon from a Colour

Pigeon to a Form Pigeon and of the Strasser from a Hen Pigeon to a

Form Pigeon (Source: Sell,

Pigeons Genetics. Applied Genetics in the Domestic Pigeon, 2012).

A source of breed mixing is also the transfer of newly discovered

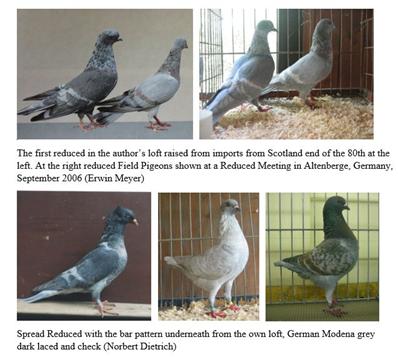

colour factors to other breeds and breed groups. Discovered in 1945

in roller pigeons, for example, the 'Reduced' factor has been

rapidly transferred in the USA to Genuine Homer, Giant Homer, Racing

Homers, Long Faced Tumblers and other breeds. It came to Europe via

such Long-Faced Tumbler crosses. In the Dortmund area the breeding

partnership Christoph Mooren

and Thomas Schmidtmann

created reduced Cologne Tumblers from these. From these the

hereditary factor was transferred by

Norbert Dietrich to

German Modenesers and by

Fritz Muchow to Colour Pigeons in Thuringian Shield Pigeons.

Thomas Voss

transferred the factor to European Racing Homers. In the meantime,

the factor is present in Owls, Drumming Pigeons and other breed

groups.

Fig. 9: Transfer of the Reduced hereditary factor

from roller pigeons in the USA to many breeds within a few years

(Source: Sell,

Critical Issues in Pigeon Breeding, Part IV 2021).

The transfer of other factors can be traced with similar accuracy in

the hobby literature. For example, for the factor indigo uncovered

in crosses in the USA in the 1940s, which was later shown to be

found in high performing European racing pigeon strains as well (Sell

2012, 2019).

Fig. 10: Transfer of the hereditary factor indigo in

a few generations to other breed groups such as high-flyers from

Racing Homers in the author’ loft and Fantails (Source:

Sell Pigeon Genetics.

Applied Genetics in the Domestic Pigeon, 2012).

At the same time as the colour factors are transferred from one

breed to the other, genes from other gene regions are also found in

this and other colour classes through crosses with them.

Molecular genetic classifications

Forms of representation

Following a study by

Stringham et al. (2012), a number of other studies have

appeared on pigeon breed similarity and classification in clusters

and representations in dendrograms. The study used 32 unlinked

microsatellite markers to genetically characterise 361 individuals

from 70 domestic pigeon breeds and two free-living populations.

Similarly extensive, and partly building on it, the study by

Pacheco et al. (2020).

Confidence-building that the tumblers and high-flyers shown here in

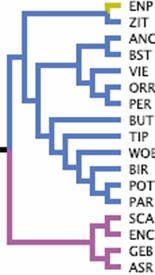

the excerpt from the dendrogram given by

Stringham, such as

Birmingham Roller (BIR), Tippler (TIP), West of England Tumbler

(WOE), remain largely together, which confirms or seems to confirm

the assumed commonality of origin.

Fig. 11: Example of a dendrogram. Excerpt from

Stringham and others

(2012). A breed classification from the English Cropper (ENP) to the

American Show Racer (ASR).

Similarity by common ancestry or recent crosses?

A proven similarity does not mean a reliable statement about the

origins of the breed. Similarity is determined between current

stock. The similarity may be due to common ancestors, it may also be

due to interbreeding between the breeds studied or between preforms

of these breeds. It is therefore not surprising that in a study

presented by a Polish research group (Biala

et al. 2015), a major finding was that the breeds studied were

subject to permanent genetic mixing.

Lexicographic classification versus classification by measuring

similarity at multiple gene loci.

The newly formed clusters are no substitute for grouping in pigeon

fancy. The English Cropper (ENP) will not be grouped with the

Stargard Shaker (ZIT) in the fancy, despite its grouping in the

dendrogram (Fig. 11). Historically, a single characteristic decides

on the grouping of pouters, drumming pigeons and tumblers/highflyers.

Pouters blow up their crop, drummer have a special vocalisation.

They are still pouters or drummer respectively, even if they differ

in size, colouration, posture and feather ornaments (cap, foot

feathering, etc.). Even with the formerly classified giant pigeons,

only this one criterion decided with the size.

The molecular genetic clustering is different. Here, a

multi-dimensional approach is chosen to define a cluster by

determining the gene regions to be included in the analysis. In

Frisch, genes

responsible for drumming, the inflation of the crop or the tendency

and ability to fly high and tumble were the only ones responsible

for group membership. In molecular genetic clustering, this is in

each case only one trait among many, which is only indirectly taken

into account, if at all.

The importance of the individuals selected for analysis

For the results of the analyses, it is important which individuals

represent the respective races. Dominant hereditary factors, for

example, can be transferred from one breed to another within a few

generations. In the case of recessive ones, it takes somewhat

longer. Even experts of the breed are often unable to detect

differences from the original breed a few generations after

crossbreeding. Individuals of one breed can therefore differ

considerably in the measured genetic distance, which is also pointed

out by Pacheco et al.

in the Supplement for their study. Breeders from Holland presented

some years ago black-winged copper Gimpel Pigeons (Archangel) into

which King Pigeons had been crossed a few generations earlier to

obtain more body mass. Even experts could not find any differences

to the pure breed. Some breeders will consider the first

cross-breeding results of a mating of a peak-crested golden-white

winged cock of the Gimpel Pigeons with a black tigered short-beaked

highflyer hen as differently coloured Gimpel Pigeons. Some of the

plain headed and peak-cested golden white wings originating from the

first back-mating upon the golden-white-wing cock were difficult to

distinguish from pure-bred birds by type, beak length and

colouration, even by experts (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: Mating of a peak-crested golden-white-wing

Gimpel cock with a plain-headed black-tigered highflyer hen with two

of their young. On the right, a female of the first back-mating to

the golden-white-wing cock at the author's loft (source:

Sell, Genetik der

Taubenfärbungen, Achim 2015).

If at first only the genome of birds coming directly from crosses

has changed, these changes will affect the whole breed through

mating with other flocks over the years. Reasons for such

cross-breeding can be colouration, feather ornaments, flight ability

or vitality in general (Sell,

2012, 2019). Especially in rare breeds with frequent breeding

borrowings from other breeds, a molecular genetic finding therefore

only represents a snapshot.

Irritations in the representation of dendrograms

There are various algorithms that lead to different dendrograms and

thus give the viewer different impressions of the network of

relationships between the breeds. Some irritating assignments to

clusters are due to the reasons mentioned above, as

Pacheco et al. also

noted with reference to background information on the animals

studied. Assignments of breeds with large genetic distances to each

other point to still other methodological reasons. So do the cases

where it could be assumed from the small genetic distance that the

breeds would quickly find themselves in a common cluster. When this

does not happen, it may be due to third party relationships. The

environment of the objects also influences the assignment.

Deletions, or even additions of races, can trigger a complete

reorganisation of the dendrogram.

Concluding remarks

For Darwin, the

historical perspective of races and the appearance of preforms

(parent stocks) were of particular importance for showing rapid

changes through selection. He was able to show this exemplarily with

outwardly extremely different breeds.

In pigeon fancying, the differentiation of breed groups was and

still is about a brief characterisation, which was usually based on

a single, easily identifiable characteristic that was considered

significant. As early as

Frisch 1763, these were and still are pouting, drumming,

tumbling, warts, special feather structures, etc. Genetic

similarities in other traits are considered secondary.

One justification for classifying breeds via molecular genetic

studies was that in pigeons, unlike other domestic animal species,

there are few reports on origin and relationships between breeds (Pacheco

et al., p. 137) are not true. The study itself refutes this

by reference to relevant literature and this is shown by the

exemplary references above. Without knowledge of the literature, it

is easy to misinterpret fresh traces from recent interbreeding as

old relationships. Conversely, old ones will be overlooked because

they have been overwritten by more recent crosses. The molecular

genetic analyses obtained are each a snapshot in time. The constant

over time for some breeds is only the breed names. Nevertheless, the

results on genetic differences of breeds remain interesting. In the

medium term, the changes in breeds over time could be monitored. And

this could possibly be done by including historical specimens.

Literature:

Aldrovandi, Ylyssis, Ornithologiæ, Bologna MDC (1600).

Biala, A., et al., Genetic Diversity om eight pure breeds and urban

form of Domestic Pigeon (columba livia var. domestica) based on

seven microsatellite loci Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 25(6):

2015, S: 1741-1745

Boitard, Pierre, et Corbié, Les Pigeons de volière et de colombier

ou histoire naturelle et monographie des pigeons domestiques, Paris

1824.

Buch der Erfindungen, Verlagsbuchhandlung Otto Spamer in Verbindung

mit Prof. Dr. Bobrik u.a., Buch der Erfindungen, 3. Band, Leipzig

und Berlin 1864.

Buffon, Georges Louis Leclerc de, Histoire Naturellee, génerale et

particulière, avec las descriptione du cabinet du roi, 1749, Vol. 4

Histoire naturelled des oiseaux, Paris 1772, Pigeons pp. 301ff.

Darwin, Charles, The variation of animals and plants under

domestication. 2 vols. 2nd edn. New York, D. Appleton & Co.

1883. [first published London, John Murray, 1868].

The writings of Charles Darwin on the web

by

John van Wyhe.

Dixon, E.S., The Dovecot and the Aviary, London 1851.

Dürigen, B., Geflügelzucht nach ihrem jetzigen rationalen

Standpunkt, Berlin 1886, Geflügelzucht, 2. ed., Berlin 1906.

Frisch, Johann Leonhard, Vorstellung der Vögel in Deutschlands und

beyläuffig auch einiger fremden, mit ihren Farben…Die Zehnte

Klasse, die Arten der Wilden, Fremden und Zahmen oder Gemeinen

Tauben, Berlin 1763.

Gesner, Conrad, Vogelbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1669, aus dem

Lateinischen mit Verbesserungen durch Georgium Horstium, Reprint

Schlütersche Verlagsanstalt und Druckerei Hannover 1995.

Gesner, Conrad, Vogelbuch. Darin die art/natur und eigenschafft

aller vöglen / sampt jrer waren Contrafactur / angezeigt wirt: ...

Erstlich durch doctor Conradt Geßner in Latein beschriben: neüwlich

aber durch Rudolff Heüßlin mit fleyß in das Teütsch gebracht / und

in ein kurtze ordnung gestelt, Getruckt zu Zürich bey Christoffel

Froschouwer im Jar als man zalt M.D.LVII (1557) (copy).

Lavalle, A., und Lietze, M. (Hrsg.), Die Taubenrassen, Berlin 1905.

Levi, W.M., The Pigeon, Sumter S.C. 1941, revised 1957, reprinted

with numerous changes and additions 1963, reprinted 1969.

Lyell, J.C., Fancy Pigeons, 3rd ed.

London 1887.

Mendel, Gregor Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden (1865) von Gregor

Mendel, Vorgelegt in den Sitzungen vom 8.

February und 8. Mach 1865) Net Version.

Moore, J., Pigeon-House. Being an Introduction to Natural History of

Tame Pigeons. Columbarium: or the pigeon house, Printed for J.

Wilford, London 1735.

Neumeister, G., Das Ganze der Taubenzucht, Weimar 1837; Das Ganze

der Taubenzucht., 3. ed. by Gustav Prütz Weimar 1876.

Reprint Verlag Neumann-Neudamm 1988.

Pacheco, G., u.a., Darwin’s Fancy Revised: An Updated Understanding

of the Genomic Constitution of Pigeon Breeds, GBE 2020.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7144551/pdf/evaa027.pdf

Sell, Axel, Taubenzucht. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen züchterischer

Gestaltung, Achim 2019.

Sell, Axel, Pigeon Genetics. Applied Genetics in the Domestic

Pigeon, Achim 2012.

Sell, Axel, Taubenrassen. Entstehung, Herkunft, Verwandtschaften.

Faszination Tauben durch die Jahrhunderte, Achim 2009.

Stringham et al., Divergence, Convergence, and the Ancestry of Feral

Populations in the Domestic Rock Pigeons, Currently Biology (2012),

doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.045.

Willughby, Francis, Ornithologia, Libres Tres, Londini MDCLXXVI

(1676);

The Ornithology in Three Books. Translated into English, and

enlarged with many Additions throughout the whole work by John Ray,

London 1678.

|