|

The

check pattern in domestic pigeons

For DARWIN, the blue-bar rock pigeon was the starting point of the

domesticated domestic pigeon. Later colourings would have developed

from blue-bar pigeons in the course of domestication. This is also

the statement of the ornithologist BECHSTEIN, who kept pigeons

himself. He believes to have observed the appearance of the check

pattern, along with other colour changes, in semi-wild pigeons in

Thuringia (BECHSTEIN 1795). In contrast, CHARLES OTIS WHITMAN

(1842-1910) placed the check pattern at the beginning. For him, the

bar pattern of the rock pigeon resulted from a 'gradual progressive

modification' in the evolutionary process. He points out the

similarity of the check pattern in the wild pigeon species, which is

particularly evident in their juvenile plumage. The development from

check to bar would also be embryonic development. In the mating of

checkered domestic pigeons, descended from the rock pigeon, over the

generations, the checks would be reduced to 4, 3, 2, 1 and 0 bars,

while in his experiments over 8 years the reverse path, from bars to

checkered birds, had remained unsuccessful (WHITMAN 1916, p. 16ff.,

162). From today's genetic point of view, however, the pathway

observed by Whitman

in the experiment, from check to bar, is not unusual if the initial

population included a heterozygous-breed individual. A more recent

molecular genetic study speculates that the check pattern was

transferred from the Guinea pigeon to the domestic pigeon after

separation of the species (an introgression). According to one

estimate, this was only 429-857 years ago (VICKREY et al. 2018). It

is therefore interesting to follow the distribution and

documentation of checkered pigeons in the literature.

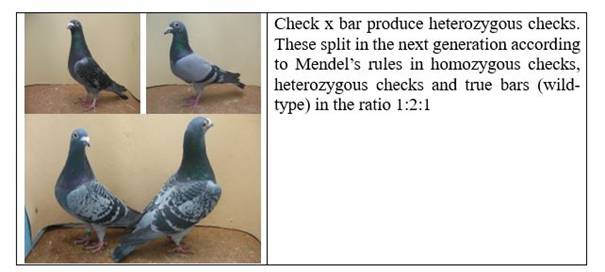

Fig. 1: Inheritance of

checker. Source: Critical Issues Part VII

Dissemination and documentation of the check pattern

In

today's city pigeons and when domestic pigeons mix with rock pigeon

populations, pigeons with the check pattern make up a large

proportion worldwide. Among Viennese city pigeons, HAAG-WACKERNAGEL/HEEB/LEISS

(2006) found a proportion of checks (31.7%) and dark-checks (24.8%)

compared to 37.3% that were barred. 4% were barless. Due to

epistatic effects (e.g. the spread factor covering pattern), 9.9%

could not be assessed. When observing feral domestic pigeons in

Kansas in 1984/85, JOHNSTON/JOHNSON (1989) found 37% barred pigeons,

compared to 22% checks and 41% dark checks. In Bangladesh wild

pigeon populations mixed with domestic pigeons, there were, among

other colors, 11% blue-checks and 75% blue-bars (KABIR 2016).

In

the early days of organized pigeon breeding and in the first

monographs on pigeons, checkered pigeons had no importance among

pigeon breeders. They were not highly regarded, with the exception

of some factor combinations with bronze or white in the check

outlines. BECHSTEIN (1795/1807) describes it as a variant of field

pigeons. In the first extensively illustrated German-language

domestic pigeon book by NEUMEISTER (1837), there is not a checkered

example among the 123 pigeons shown on the plates. However, the gene

for checks may have been present in the so-called white blaze with

whitish or bronze wing shields. In the text, the drawing contour of

the checks appears under the 'meliert' pigeons listed after the

field pigeons in the text, based on BECHSTEIN. Among these also

mentioned are larks and laced ones. The former were probably

preforms of lark-pigeons, the latter of the later scaled (laced)

lynx pigeons. BREHM (1857, p. 92) describes 'carp-scaled' and

'hammer-faced' pigeons among the field pigeons with which they were

associated but formed a minority. PETER PAILLOU had already

presented an early drawing of a Parisian Pouter with similar scales

in England in 1744. Similar to the Pigeon Maillés created from

pouters in BOITARD/CORBIÉ 1824 (p. 179ff.) as preforms of the later

Cauchois.

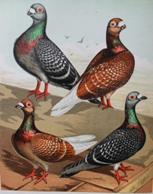

Fig. 2: Paris Pouter with

the check pattern by Peter Pailou 1744. Fig. 3: Color Pigeons at

Neumeister 1837

However, drawings of blue checks existed even earlier. If you go

back 429 years, the lower limit for potential introgression

mentioned above, then you are in the time of MARCUS Zum LAMM

(1544-1606). In Freiburg (Germany) he had pictures painted for his

Thesaurus Picturarum and put together a collection. Also mentioned

in his notes is a 'Visch Schüppichte or hammerschlegichte Daub'.

This was apparently a common name for checks in the region. One of

his pictures that has been preserved is a drawing of a blue-check

field pigeon. There must therefore have been checkered domestic

pigeons long before this time, as they were already common terms at

the time. If we go back 857 years, we are shortly before the time of

EMPEROR FREDERICK II (1194-1250), who wrote his Falcon Book between

1241-1248. It was completed by his son. In addition to turtle doves,

the numerous miniatures also contain two domestic pigeons, which can

be classified as checkered when compared to the blue-bars shown.

Even further back, the restored murals in Akhenaten's North Palace

in Amarna (around 1350 BC) in Egypt show, among other things, a blue

pigeon, which HAAG-WACKERNAGEL (1998, p. 46f.) classifies as

checkered. Overall, the evidence from the past gives the impression

that checks in domestic pigeons occurred mutatively in different

places at different times, as BECHSTEIN describes it.

Fig. 4: Blue check field

pigeon, Marcus Zum Lamm about 1600.

Source: Kinzelbach/ Hölzinger 2000. Fig. 5: Blue check pigeon in the

North Palace of Echnaton in Armarna, Egypt about 1350 BC. Source:

Haag Wackernagel 1998

Fig. 6: Checkered Dovecot Pigeon (Albin 1735). Fig. 7: Checkered

Dovecot Pigeon (Dixon 1851)

Good

conditions were found for checks, kept semi-wild, apparently at the

time of ALBIN, who drew a checkered pigeon in 1735 as a

representative of the 'Dove House' pigeons in England. A good 100

years later, DIXON describes her as a typical inmate of the English

'Dovecots' (DIXON 1851, p. 162ff.). According to DIXON, the

checkered variant had already successfully established itself under

railway overpasses in London and other parts of England. This

suggests advantages for the checks in the fight for survival as

urbanization increases.

The

increase in reputation and thus the spread in hobby breeding will be

linked to the spread of the Belgian racing pigeon after 1800. In

connection with this, from the second half of the 19th century

onwards, the breeding of racing homer-related fancy breeds such as

the Show Antwerp, Show Homer, Show Racer, the German Beauty Homer,

etc. On the 50 color plates in the magnificent work by FULTON (1876)

there are two color plates with checkered homing pigeons (in England

called 'Flying Antwerp' because of the imports via the port of

Antwerp form Belgium), and Show Antwerp. On the other panels there

is only one checkered one, namely a blue check shield owl. In

combination with white scales, the gene for checks can also be seen

in pictures of Oriental Owls, Hyazinth, Starlings and Ice Pigeons.

Fig. 8: Show Antwerp and Flying

Antwerp (Belgian Racing Homer). Fig. 9: Oriental Owls with the bar

and with the check pattern. Fig. 10: Hyazinth Pigeon and Starling

with the check pattern. Source: Fulton 1876

Hybrids

with Guinea pigeons

WHITMAN had already pointed out the similarity of the checkering of

the Guinea pigeon with the typical light triangular spot at the end

of the feather in the shield with the checkered of some, but not

all, domestic pigeons. A similar checkering can be found in many

wild pigeon species. In addition to the widespread turtle dove,

whose checks WHITMAN considers to be the archaic form of checks in

the pigeon family (p. 50), the special checkering of the Guinea

pigeon can also be found, among others, in Columba maculosa and C.

albipinnis (p. 163).

Hybrids of Guinea pigeons with domestic pigeons and reverse matings

were analyzed in blood group studies of pigeon species. So, in 1936

by IRWIN, COLE, GORDON as well as MILLER/BRYON 1953 and LABAR/IRWIN

1967. Among others, five different antigenic substances were

identified as putative inheritance units that were specific for the

Guinea pigeon (MILLER/BRYON 1953, p. 407). Hybrids with barred

domestic pigeons showed the check pattern and also the loyalty of

the racing pigeons to the location of the own dovecote (COLE CREEK

2019). Problems in maintaining and raising hybrids and early

mortality are reported (see also GRAY 1958). Some of the hybrids are

viable and capable of reproduction, even when mated back to domestic

pigeons.

Fig. 11 and 12: Guinea

pigeon and Hybrid-hen, lost by illness. Held and flown with the

Racing Homer team. Source: Cole Creek at Facebook. Fig. 13: Columba

maculosa, Lip Kee Yap, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>,

via Wikimedia Commons.

Diffusion of mutation and introduction of genes through hybrids

Similar behavior, the possibility of obtaining fertile hybrids, and

the visual similarity to the checks of the domestic pigeon led to

speculation that the pattern was transferred from the Guinea pigeon

to domestic pigeons. In view of the sparse references specifically

to the checkered pattern in domestic pigeons from the past, this is

not an unfounded hypothesis. Mathematical model calculations show

how quickly superior genes, whether created through mutations in a

population or added through crossing, can prevail when partners are

chosen at random. A dominant factor will reach a proportion of

around 50% after 400 years with a constant population and number of

offspring (per parent) of 5, an advantage of the carriers of the new

trait of 1/100 and an initial frequency of the new gene of 1/1000 (Mittmann

quoted from KÜHN 1961, p. 250). Random mating can be assumed in

feral domestic pigeons and, with regard to coloring, in racing

pigeons that are primarily selected for performance.

For other breeds, breeders' different selection

criteria play a role. In breeding groups in which new factors have

been introduced, the factor will combine with other existing ones

over the generations. Let's assume that in a population of pigeons,

Smoky is present alongside the wild type. Then after a short time

the proportion of pigeons with the smoky factor should not differ

between checkered and barred pigeons. Close genetic linkages that

could hinder mixing over centuries are unlikely. Regionally, there

will be differences in genetic makeup in subpopulations due to

spatial distances, other environmental conditions, factor

interactions that are not directly recognizable, threats from birds

of prey, etc. (SANTOS et al. 2015). Such differences have also been

found between feral domestic pigeon populations in the megacities of

the northeastern United States from Boston to Washington (CARLEN et

al. 2021). For example, in tests in which the proportions of certain

factor combinations are important, it will make a difference if, for

example, barred individuals are chosen from a different region or

from different breeds than checkered individuals.

In

the case of introgression, the main difference to mutation within

the species is that, along with the gene under consideration, the

hybrids are heterozygous for other hereditary factors. Some of them

were not present in the host population until then. Most of them are

probably not visible externally. They could be immunities, genes

that influence energy metabolism, etc. They could be

species-specific and, in the species that transmits the gene, have

emerged mutatively after establishing as a separate species. If

transmitted to domestic pigeons, many factors will disappear

quickly, but others will become established and possibly expand

significantly. The diffusion is likely to start from the point of

origin, similar to a mutation, and spread regionally over time.

However, under human care, distances do not play a role for newly

discovered mutations, as the Reduced example shows (SELL 2012,

2021). In subpopulations into which these factors have penetrated,

they will freely combine with each other and with those present, as

in the spread of mutations.

Measuring introgression

ABBA-BABA tests: In evolutionary

research, potential introgression is usually analyzed using

ABBA-BABA tests, in which four populations are compared with each

other (DURAND et al., 2011). There are two currently existing

populations P1 and P2. Then an evolutionary older population P3 and

a fourth outgroup population O. This is more distantly connected to

these three ingroup populations. Their genome serves as a reference;

their gene expression at the compared loci is designated A. The

alternative that P3 has is called the 'derived allele' and

symbolized by B. The null hypothesis for the empirical test is that

P1 and P2 diverged from a common ancestral population that had

separated from the ancestral population of P3 at an earlier time.

After P1 and P2 split off from the ancestors of P3, there was no

gene flow from any of the groups with P3. The alternative hypothesis

is that P3 exchanged genes with P1 or P2 after these two populations

separated (DURAND et al. 2011, p. 2240). If the null hypothesis is

true and the ancestral populations of P1, P2, and P3 were equally

likely to interbreed without selection differences, then the derived

alleles in P3 should match those in P1 and P2 with equal frequency

and the D-statistic of the ABBA-BABA test should be zero result.

Significant deviations from zero would require an explanation, which

could be an introgression from P3 to P1 or P2. Alternatively, from a

'ghost population' PG very similar to P3, which may no longer exist

(DURAND et al. 2011, 2040).

Repurposing the ABBA-BABA test to color classes or specific genes:

In the study by VICKREY et al. In 2011, the broader ABBA-BABA

methodology will be repurposed to address the specific question of

whether the domestic pigeon's check pattern was transferred from the

Guinea pigeon. In the experimental setup, P1 are barred domestic

pigeons, P2 are checkered domestic pigeons. P3 is the exclusively

checkered Guinea pigeon. The Wood Pigeon was chosen as the outgroup.

P1 and P2 are therefore not different species that mainly reproduce

among themselves, but rather different colors of the domestic

pigeon. In his studies in 1939, HARMS did not attribute their own

racial character to these (p. 11). The calculation requires the

identification of transferred (derived) genes or those that are

believed to be such. When mated randomly and maintained in symbiosis

over long periods of time, the expectation is that 'derived' and

putative 'derived' alleles will be distributed equally between

barred and checkered individuals.

Significance of the studies for color variations of domestic pigeons

The

checkered pigeon in the English Dovecots was given its own status by

BLYTH as C. affinis during DARWIN's lifetime, which DARWIN (1868)

denied with many arguments. He considered the barred version of the

rock pigeon to be the older one. For WHITMAN it was the other way

around (p. 49). When repurposing the ABBA-BABA tests to domestic

pigeons, checkered pigeons are treated as a separate population.

Coming from animal breeding, it's hard to imagine that barred and

checkered animals, which have lived in symbiosis for centuries, are

systematically different from one another. An exception is the genes

that determine the pattern. The regionally delimited Viennese city

pigeons, which form a reproductive community, may form a population,

but not individual colors from it. Unless there is a strong affinity

when choosing a partner for the same pattern. The study cites, among

other things, the study of feral domestic pigeons (ferals) by

JOHNSTON/JOHNSON 1989 to prove an affinity. This suggests, however,

shows that there is a greater preference of bar and check to

intermix through their choice of partner. In the fancy, breeding for

shows, the standard encourages a pairing of barred and checkered

animals. Heterozygous check individuals usually correspond more to

the standard expectations with open checks than homozygous ones.

This is also an incentive to pair both colors with each other.

On

the empirical side: For the gene region in which the patterns are

anchored, the D statistics show values close to one. In terms of

measurement, these gene areas of the checkered domestic pigeon

largely correspond to the gene areas of the Guinea pigeon and check

is the central 'derived allele' from the original question. One

difference is that no repeats of gene sections (copy number

variation) were found in the Guinea pigeon (VICKREY et al. 2011).

For the whole genome, D-statistics values close to zero were

determined. Positive at 0.021, which is considered an indication of

introgression from P3. It is not possible for outsiders to recognize

which phenotypes or characteristics are behind the suspected

“derived alleles” and how many there are in the sample. In the case

of rare genes, drift in the populations will cause problems in

clearly identifying “derived” alleles. Based on what is known so far

about genetic linkages and correlations and about the pigeon's

mating selection, deviations in D values from zero require

explanation. As with mutations, they could also be due to chance and

sample selection. Rare archaic genes, present or lost in varying

proportions across species due to genetic drift, could be confused

with derived alleles. Overall, a manageable number of individuals

were examined. Significance at low D-values can be achieved with a

moderate number of analysed individuals if several gene loci are

considered in each case. The mathematical sample size, which is

important for the formal significance statement, thus increases

multiplicatively.

Summary

The

proportion of checkered pigeons among domestic pigeons has increased

significantly in recent centuries. It is therefore interesting to

investigate possible causes and the question of whether the check

pattern got into domestic pigeons through mutation during

domestication or through hybridization with the Guinea pigeon. From

an animal breeding perspective, it is rather questionable whether

ABBA-BABA tests can be of any methodological help for this question.

Checkered and barred domestic pigeons do not form separate

populations. They are different colors of a reproductive community

in city pigeons and racing pigeons. Pigeons do not have such a

strong affinity when mating within identical colors that, according

to previous findings from crosses between breeds and studies of

genetic linkages, potentially acquired (derived) alleles remain

connected for centuries. Perhaps molecular genetic studies will soon

say more about this and/or something different. The question of

'derived' alleles is closely linked to the question of whether one

can imagine that mutations repeat themselves. This is assumed to be

excluded in DURAND's methodological presentation. If this is the

case, then the exclusive existence of the gene in the receiving and

releasing population, be it checkered or barred, can be a strong

indication, regardless of the value of the D statistic, viewed

alone. WHITMAN (p. 19) considered the check pattern to be an

ancestral feature of the phylum of pigeons, which was modified in

the barred rock pigeon by direct and gradual modifications. If the

programming for checks is preserved in the genome, the trait could

be activated by parallel selectively triggering mutations, which

could explain, for example, a surprisingly rapid parallel fixation

of traits in a parallel evolution of separate populations in

cichlids (Urban et al. 2020, p. 466). It is possible that parallels

can be found in other animal species.

Literature:

Albin, Eleazar, Natural History of Birds.

Illustrated With a Hundred and one Copper Plates, Engraven from the

Life, published by the Author and carefully colour’d by his

Daughter and Himself, from the Originals, drawn from the live

Birds, Vol III London MDCCXXXVIII (1738)

Bechstein, Johann

Matthäus, Gemeinnützige Naturgeschichte Deutschlands nach allen drey

Reichen, 4. Band Leipzig 1795

Bechstein, Johann

Matthäus, Gemeinnützige Naturgeschichte Deutschlands nach allen drey

Reichen. Ein Handbuch zur deutlichern und vollständigern

Selbstbelehrung besonders für Forstmänner, Jugendlehrern und

Oekonomen, Dritter Band, Mit Kupfern, Zweite vermehrte und

verbesserte Auflage, Leipzig 1807

Brehm, Christian

Ludwig, Die Naturgeschichte und Zucht der Tauben, Weimar 1857,

Reprint Leipzig 1981.

Carlen E, Munshi-South J. Widespread genetic

connectivity of feral pigeons across the Northeastern megacity. Evol

Appl. 2021;14:150–162. https://doi. org/10.1111/eva.1297

Darwin, C. R. 1875. The variation of animals and

plants under domestication. London, John Murray. 2d edition. Volume

1

Darwin, Charles, The variation of animals and

plants under domestication. 2 vols. 2nd edn. New York, D. Appleton

& Co. 1883. [first published London, John Murray, 1868].

The writings of Charles Darwin on the web by

John van Wyhe.

Dixon, E.S., The Dovecote and the Aviary, London

1851

Durand, Eric et al., Testing for Ancient

Admixture between Closely Related Populations, Mol. Biol.

Evol. 28(8):2239-2252, 2011

Friedrich II, Das

Falkenbuch Kaiser Friedrichs II. Über die Kunst

mit Vögeln zu jagen - Süditalien, 1258-1266; After the magnificent

manuscript in the Vatican Library. Introduction and commentary by

Carl Arnold Willemsen, Harenberg. Dortmund 1980

Goodwin, Derek, Pigeons and Doves of the World,

British Museum (Natural History), 2nd edition London 1970

Gray, Annie P., Birds Hybrids, A Check-List with

Bibliography, Bucks, England 1958

Haag-Wackernagel,

Daniel, Die Taube. Vom heiligen Vogel der Liebesgöttin zur

Straßentaube, Basel 1998

Haag-Wackernagel, Daniel, Heeb, Philipp and Leiss,

Andreas (2006) 'Phenotype-dependent selection of juvenile urban

Feral Pigeons Columba livia, Bird Study, 53: 2, 163 — 170: DOI:

10.1080/00063650609461429; URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00063650609461429

Kabir, M. Ashraful, Rock-Pigeons in Some Parts of

Bangladesh, The Journal of Middle East and North Africa

Sciences 2016; 2(3) http://www.jomenas.org

Kinzelbach, Ragnar

K. und Jochen Hölzinger (Hrsg.), Markus zum Lamm (1544-1606), Die

Vogelbilder aus dem Thesaurum Picturarum, Ulmer: Stuttgart 2000

Kühn, Alfred,

Grundriss der Vererbungslehre, 8. Auflage,

Heidelberg 1961

McGill Library Archival Collections, Pariser

Kröpfer, Peter Paillou (1720-1790)

Santos, C. D. et al., Personality and

morphological traits affect pigeon survival from raptor attacks. Sci.

Rep. 5, 15490; doi: 10.1038/srep15490 (2015).

Sell, Axel, Critical Issues in Pigeon Breeding.

What we know and what we believe to know. Anecdotal, Entertaining,

and educational comments on open questions Part 1-7, Achim 2020-2023

Sell, Axel, Pigeon Genetics. Applied Genetics in

the Domestic Pigeon, Achim 2012

Sell, Axel,

Taubenrassen. Entstehung, Herkunft, Verwandtschaften.

Faszination Tauben durch die Jahrhunderte, Achim

2009

Urban, Sabine, et al., Different Sources of

Allelic Variation Drove Repeated Color Pattern Divergence in Cichlid

Fishes (University of Konstanz), Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(2): 465-477

Advance Access publication September 17, 2020

Vickrey, Anna I. et al., Introgression of

regulatory alleles and a missense coding mutation drive plumage

pattern diversity in the rock pigeon, eLifesciences.org 2018

Whitman, Charles Otis (1842-1910), Orthogenetic

Evolution in Pigeons, Posthumous Works edited by Oscar Riddle, Vol.

I, The Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington 1919. Bird

Study (2006) 53, 163–170, © 2006 British Trust for

Ornithology

Wikipedia, Columba maculosa. Lip Kee Yap, CC

BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via

Wikimedia Commons

|