|

Breeding for Black: Dull and Deep 100 years ago

Weakly coloured blacks

From the mating of blue-bars or checks with self blacks and other

colours with the colour spread gene often also dull grey-blacks with

dark-black set-off bars or checks are produced. Often with set off

tail band (Fig. 1). That was still documented by Sarah van Hoosen

Jones about 100 years ago. In contrast to theory? Shouldn't Spread

as the dominant gene cover the pattern 'bars' and possibly the

'checks'? According to Radio Eriwan: In principle yes, but

... Spread often only partially covers the pattern. And whether, and

to what extent, depends on other modifiers. In the chapter on

Toy-Stencil for example, one will learn that the bars or checks in

blacks even stand out strikingly.

Back to Non-Toy-Stencils. Weakly coloured blacks from experiences in

practice are not mutants, Spread is not lacking. When only the check

pattern instead of bars is genetically present under the weak black,

the colouration becomes more uniform, but not as intensive like in

deep black. At dull black not only bar patches but also the check

spots stand out on the wing shield on a grey ground colour. In the

case of checks and T-check birds, this also makes the entire wing

shield darker (Fig. 3). The darker bars and check marks of the

weakly coloured blacks correspond to these markings in blues.

Paradoxically at first sight, in 'Toy Stencil' it is precisely these

bar and check spots that are strikingly 'printed' white through the

black ground colour (for details see ‘Pigeon Genetics’ and ‘Genetik

der Taubenfärbungen). However, by many of them the color never

becomes as intense as in deep-black individuals.

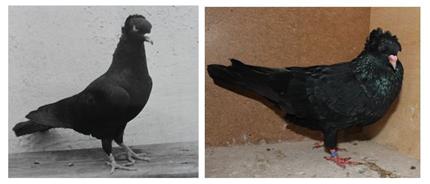

Fig. 1 und 2: Weaker coloured female hen with translucent bars and

lightened edge feathers with visible tail band (source: Sell,

Genetik der Taubenfärbungen 2015, there fig. 221). On the right

translucent bars, no distinct tail band and no white outer vane,

from the mother-side heterozygous smoky. Both heterozygous spread

from a blue parent from the stock of the author.

Fig. 3: Black with translucent checks from the own loft,

heterozygous for Spread, Dirty and Smoky

100 years ago: Deep-Black

A darkening of the black appearance is also achieved by Dirty and

Smoky. However, expectations should not be set too high. Smoky, for

example, may be helpful to blur contrasts of the translucent

patterns with the moult. Nevertheless, the author, for example,

initially also had only weakly coloured smoky blacks in his breed

(Fig. 5).

Other factors intensifying the colour and gloss had to be added, for

which indications were already found in the literature in 1922.

Sarah van Hoosen Jones dealt among others with the modification of

the depth and sheen of the color of many black birds and thematised

‘Deep’ as a factor responsible for intense and uniform colouration.

She distinguished the blacks into two groups. The weaker coloured

blacks were called 'dull'. And, with underneath checks, ‘dull black

checks’ (Fig. 4). Whether the alternative 'Deep' is an allele of

Spread suspected in the literature or, as indirectly stated in the

article, a modifier acting on Spread, is open. According to one's

own assumption, it is more likely the interaction of several

modifiers. Dull without translucent pattern are not excluded by van

Hoosen Jones either, and some weaker coloured own black homing

pigeons also genetically had the bar pattern.

Fig. 4: Dull black check at Sarah van Hoosen Jones 1922

Conversion of a strain from 'Dull' to 'Deep'

When traditional attempts to improve colouration are not enough, the

only option is to add intensity factors from other breeds in the

style of 'new breeding'. Traditionally means are many years of

selection with the aim to weed out negative modifiers and enrich

positive ones. Since that did not work, the introduction of the

lacking modifiers was the option.

Fig. 5: Black smoky Pomeranian Highflyers, at the left with weak

colour, at the right after upgrading by outcrossing. Source: Sell,

Genetik der Taubenfärbungen, there fig. 253), Achim 2015.

In this way, a largely uniform and intense (deep) black strain has

indeed been achieved (Fig. 5). As is shown in breeding, uniform and

intense colored deep-black may be underneath genetically bar pattern

and also heterozygous Spread only.

Fig. 6: Deep (left) and dull (right) from the own loft. At the right

a heterozygous Spread, heterozygous Smoky from a blue-bar wild-type

cock.

Uniformly coloured in these intensely coloured blacks are also those

'Deep', which genetically have the bar pattern in the background.

Occasionally the bars show slightly in the juvenile plumage

and depending on light. Largely uniform are also those that are only

heterozygous for the spread factor. This is confirmed by the blue

juvenile from the black old bird in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7: Black adult cock and young blue bar as indicator for

heterozygous Spread

Black without Spread

Not only are there genetic blacks that do not look black to

outsiders, there are also blacks that genetically do not have

Spread. This is the case with the wings of the black-winged Gimpel-Pigeons.

After crosses with blues and blue-checks there are checkered ones in

the first generation, and there are no blacks in successive matings

either. Deep blacks without the spread factor were also kites in the

author's Danish Brown Stipper breeding (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Danish Tumblers, Brown Stipper-cock and Kite hen from the

author’ former strain

For black Starling pigeons it is often written in literature that

they do not have Spread. This does not seem to have been documented

by meaningful photos and succession matings of a first generation so

far. Thus, confusion with weakly coloured blacks of the first

generation - as shown at the beginning - cannot be excluded.

Observations have also been made in black Gazzi of the Italian

Modenese, which indicate the absence of spread. So, there are still

mysteries to be unravelled.

Literature:

Sell, Axel, Pigeon Genetics. Applied Genetics in the Domestic

Pigeon, Achim 2012, www.taubensell.de

Sell, Axel, Genetik der Taubenfärbungen, Achim 2015.

Van Hoosen Jones, Sarah, Studies on inheritance in pigeons IV,

Genetics VII 1922, pp. 466-507.

|