|

Can

we preserve our breed diversity in the pigeon fancy?

Many

breeds and colors and less and less breeders, how does that fit? One

cannot change the development of the number of breeders. The leisure

behavior has changed, including the housing conditions. Who can

raise in the block of flats, terraced house or even in a detached

single family house, with today often almost 400 square meters of

land or less, still pigeons, without having to fear problems with

the neighbors! Finally, new diseases create uncertainty and

veterinary regulations are becoming increasingly complex. Private

animal husbandry also is under attack of animal welfare circles; pet

owners are not perceived as allies with regard to preserving the

natural foundations of life for humans and animals. The thinning of

the number of fanciers in the individual breeds and the

disappearance of some breeds seems inevitable. Even if one follows

the advice of some, no longer to allow additional foreign and new

breeds. That breeds should be sufficiently different, is already in

the conditions anyway.

Can

you oblige breeders to preserve what others have considered to be

beautiful before them? Many certainly want to decide themselves and

pursue their own ideas. You cannot force these breeders.

The

disappearance of domestic pigeon breeds is dramatized by a parallel

to the extinction of species. Is it real that breeds cannot be

re-established once they disappear? The parallels with the

extinction of species is an inadmissible comparison. The extinct

Passenger Pigeon will not be brought back to life. Most of the

breeds of domestic pigeons, all of which originate from mutations

and selections from the rock pigeon, may come back since they have

many characteristics in common with other existing breeds. In the

event that the Oriental Blondinettes should one day die out among

the Oriental Frills, the Greek Caridia in 1876 has already left us

the recipe for the breeding from Satinettes and African Owls. Within

two decades, they were brought to the level that was - perhaps

somewhat idealized - captured by Ludlow in the Illustrated Book of

Pigeons, edited 1876 by Fulton (Fig. 5 below). Even if a muffed

color pigeon breed should disappear, you can breed a similar pied

marked breed in a few generations with heavy muffs. The kind of

flying and tumbling of the Oriental Roller may be different. The

mutations responsible for the particular flight behavior will not be

easy to repeat. However the flying style is generally not preserved

by fancy breeders and through exhibitions, but by the highflyer and

roller community.

Statements that with the extinction of a pigeon breed, all

properties are irretrievably lost and the breed is no longer the

same since by crossing with other breed the character changes,

become a boomerang for the entire fancy and the myth prevailing in

some circles on what we do in the fancy. The competition at the

exhibitions is designed for change, and these changes are

essentially achieved through crossings with subsequent selection.

Keeping old cultural heritage unchanged is something else. Whoever

does not want to perceive this as a fact and claims otherwise, lies

to himself and others. Alois Münst addressed this topic in the

volume 1 of the anthology ‘Alles über Rassetauben’ edited by Erich

Müller years ago under the keyword "preserving breeds or breed

names". Compare for example Strasser, Lynx, Maltese Pigeons,

Modenese Pigeons or, in the tumbler section, Danish magpies in

illustrations more than 100 years ago and today. How and with what

other breeds for outcrossing these changes have been achieved is

sufficiently documented in the relevant historical literature.

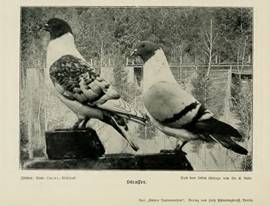

Fig.

1: Strasser at Lavalle und Lietze, Die Taubenrassen, Berlin 1905,

and from today

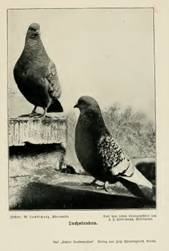

Fig.

2: Lynx at Lavalle and Lietze, Die Taubenrassen, Berlin 1905, and

from today

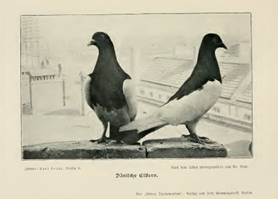

Fig.

3: Danish Tumbler black magpies at Lavalle and Lietze, Die

Taubenrassen, Berlin 1905, and from today

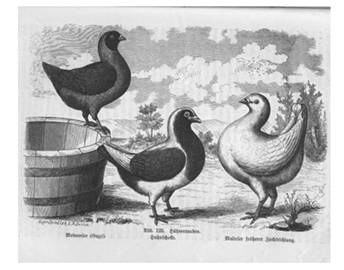

Fig.

4: Modena, Hungarian und Maltese old type (from left to right) at

Dürigen, Geflügelzucht 2. ed. Berlin 1906, and Maltese from today

At

some distance, the modern types in Figures 1-4 appear rather like

new breeds, rather than as a result of the traditionalists' desire

to preserve ancient cultural heritage.

It can

also be seen from the literature that over the century breeders have

experienced the interaction with pigeons and competition and

camaraderie as a meaningful hobby. They also gained a lot of

insights into the biological basis and left written record of

experience, thereby contributing to the deciphering of our genetic

knowledge. To use an ancient Chinese wisdom: ‘The way is the goal’,

the contact with the pigeons and handling them. Only exceptional it

will be possible to reserve in life intermediates in breeds’

development. Here lies the value of historical literature, in which,

as for many breeds also e.g. in the ‘Fulton’, the chosen paths and

experiences are documented.

Fig.

5: Blondinettes from the ‚Illustrated Book of Pigeon’, edited by

Robert Fulton 1876; Collected knowledge in the national and

international pigeon literature

New

color-classes are something different than new breeds, though often

thrown together in the discussion. For those who have bred only one

color throughout their lives, crossing with another is an

incalculable adventure. They should, however, allow others to see a

special charm in diversity and not to forbid them to breed. From the

so called ‘new’ color-classes, which are also often problematized,

only a few are really new. So for Germany a few decades ago the

Indigo color-classes inclusive of Andalusians, then Reduced, others

may follow. Probably it was not possible to prevent them since

otherwise interested fanciers would have formed outside the

organization genetic groups for rarities. However, most of the other

colors shown in the new breeds sections for getting accepted as

standard-colors are not new to the breeders, they appear

automatically when breeding other accepted colors with each other.

Thus e.g. recessive yellow and black may produce dun hens in the

first cross. And do they really harm the breed? The only question

here is how much organizational effort should be put into

recognizing color-classes. Does every Indigo color pattern, barless,

bar, check, and dark check, really need to be recognized

individually? Even though a genetically experienced breeder knows

that the other color-classes automatically occur by crossing with

the blue-color series when you have one of the indigo pattern

variants? The Federal Breeding Committee could certainly make better

use of its time than wasting it on the idea of new ‘old’ colors.

Literature:

Dürigen, Bruno,

Geflügelzucht, 2. Auflage Berlin 1906.

Fulton, Robert, The Illustrated Book of Pigeons, London, Paris, New

York and Melbourne 1876.

Lavalle, A., und M.

Lietze (Hrsg.), Die Taubenrassen, Berlin 1905.

Münst, Alois,

Tradition pflegen – alte Rassen bewahren, in: Erich Müller (Hrsg.),

Alles über Rassetauben Band 1, Entwicklung, Haltung, Pflege,

Vererbung und Zucht, Oertel+Spörer 2000, S. 368-381.

Sell,

Axel, Pigeon Genetics. Applied Genetics in the Domestic Pigeon,

Achim 2012.

Sell, Axel,

Taubenrassen. Entstehung, Herkunft, Verwandtschaften. Faszination

Tauben über die Jahrhunderte, Achim 2009.

Sell, Axel,

Taubenzucht. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen züchterischer Gestaltung,

Strukturen, Figuren, Verhalten, Zucht und Vererbung in Theorie und

Praxis, Achim 2019.

|