|

Pigeon colours

The first names

Names for colours in pigeons

usually have little in common with the colour names in everyday

life. The names should not and could not be more than a rough

orientation. More than 100 years ago, the geneticist Cole had

already noted this for the original colour blue: The blue of pigeons

also has nothing in common with the blue of some exotic birds, it

belonged more to the grey tones (Cole 1918). Bechstein had already

felt this earlier. In 1807 he wrote of 'light greys' and 'dark ash

greys' without it having any influence on subsequent literature. The

latter possibly today's smoky or dirty blues. Also, under 'red'

pigeon fanciers imagine something different than a master painter

would. He would think of pigeon red as brown or bronze. White, black

and yellow are more harmless.

Fig. 1: Blue Rock Pigeon, Black, (Recessive) Red

and Yellow at Domestic Pigeons

Newcomers and outsiders will

not be able to change much in terms that have been introduced,

because they have burnt themselves deeply into the literature and

the language of pigeon keepers over the centuries. For example, in

his Ornithology, published in Latin in 1555 and in German in 1557,

Gessner already wrote of blue, red, waxy yellow, mealy and

sparrowhawk colours for domestic pigeons. In addition to white and

black, various piebald colours were described, which Bechstein

presents in 1807 in a very differentiated manner.

Names for exceptional colourings.

With the diffusion of

domestic pigeon breeding and the diversification of the range of

colours, there was also a need to emphasise colours that were

considered exceptional. Buffon's colours in France in 1772 included

among others fire colour, chestnut, walnut and hyacinth at Pouter

(Pigeon Grosse Gorge) as ancestors of the today laced Cauchois.

Boitard and Corbié additionally listed the peach-flower-coloured

ones among the 'Pigeons Maillés', already removed from croppers in

1824. They also already recognised genetic connections. From the

crossing of bronze-laced and white-laced pigeons, walnut-coloured

ones are produced. The mating of these back to white-laced results,

among others, in peached flower ones (p. 32). On the breed see

Jürgen Schulz, Cauchois. Portrait of a French Breed Pigeon, German

language, published by the Special Club 1987).

Fig. 2: Cauchois peach blossom coloured, bronze

laced, at Buffon’s time fire coloured) and blue white laced (at

Buffon’s time hyazinth)

Fig. 3: English Almond Tumbler (Eaton, J.M., A

Treatise on the Art of Breeding and Managing the Almond Tumbler,

London 1851), English Short-Faced Tumblers Kite and Rot Agate.

In the German-speaking

world, 'Harlekins' was the name for variegated pigeon, some of which

resembled the Almond Tumbler in England with a yellow-brown (almond)

desired basic colouration. The black sprinkles and brightenings in

the primaries and tail are typical for all of them. Tricolour was

supposed to say something similar in old literature. Reds with white

spots in the Almond breeding were given the name Agate after the

often red and white gemstone, Kites as a second complementary colour

were named after the black milan.

Isabell was so popular as a

name that it was given to at least four gene combinations that are

distinguished today. For a long time it was not known why the

breeding results of some variants were so poor.

Lavender was a popular name.

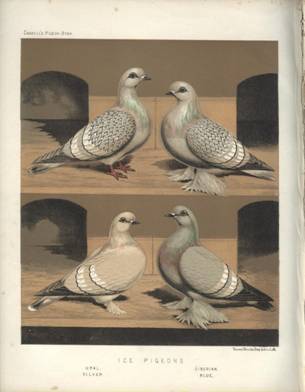

Tegetmeier (1868) used it, Fulton described self barless Ice Pigeons

this way in 1876. Later the term briefly passed to khaki pigeons (Metzelaar

1928), and in English to (heterozygous) ash pigeons and light

silver-grey Lahores (Levi 1969).

Fig. 4: Ice Pigeon Varieties at R. Fulton, The

Illustrated Book of Pigeons, London, Paris, New York, Melbourne

1876.

The name gold was probably

first claimed for gold gimpel-pigeon, copper for copper gimpel-pigeons,

bronze as a synonym for the description of the body plumage of

copper gimpels (Schachtzabel 1910).

Fig. 5: Gimpel Pigeons Blackwings Copper and

Gold; Maltese Pigeon Gold (genetically different from Gimpel-Pigeons,

the combination of homozygous recessive red and homozygous pale)

Naming of hereditary factors

Almond, Isabell, Lavender,

Peach Blossom, etc., were intended to indicate similarities of the

respective colour, independent of genetic considerations or

commonalities with other colourings. In pigeon fancier circles

before 1900 and shortly thereafter, nothing was known about

hereditary factors that were responsible for the similarities of

certain colourings. It was only with the spread of Mendelian thought

that genetic 'codes' were searched for, for the combination of

hereditary factors that produced this colouring, and in slightly

different combinations, similar colourings. A puzzle, the solution

of which made it easier to selectively breed colours.

Sprinkles - Stipper

For Almonds, the puzzle of

sprinkling and the regular occurrence of white juvenile cocks in

breeding was solved as early as 1925 by Christie and Wriedt. They

did not intend to clarify the Almond colouration genetically, but to

a large extent they did. They wanted to find the causes of

sprinkling in domestic pigeons. For this purpose, they had not only

analysed almonds in breeding trials, but also sprinkled grey

stippers and other intermediate colourings. Danish Tumblers with the

stipper gene (Staenkede), which originated from crosses with English

almonds, were examined. Today there are Brown Stippers, Yellow

Stippers and Grey Sippers in the standard terminology. Brown and

yellow stippers correspond to a large extent to English almond

Tumblers and partly to multicoloured Tumblers. As a result, all

colourings were found to have a factor which, according to the

findings, temporarily (in the heterozygous cocks and, sex-related,

hemizygous females) or almost completely (in the homozygous cocks)

restricts pigment formation or supply to the feathers (Hollander

1983). The homozygous Stipper-cocks are accompanied by health

problems. Almonds are thus stippers in which the brown-yellow basic

colouration is contributed by the genes of the already mentioned

complementary colours kite (dark check and bronze) and agate

(contribution of heterozygous recessive red). In the USA, the symbol

St was adopted, derived from Staenkede. For a long time, however,

the term ‘Almond factor’ was used, probably because most breeders

were not aware of the other sprinkled colour strokes at that time.

Even today, most breeders are not aware of the connections.

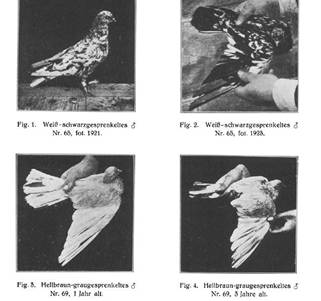

Fig. 6: Danish Tumblers tested by Christie and

Wriedt. Source: Zur Genetik der gesprenkelten Haustaube.

Zeitschrift für Induktive Abstammungs- und Vererbungslehre 38 (1925)

in German language. Figures hite with black sprinkles at different

age (1 and 2) and ‘light brown grey sprinkled’ (3 and 4) at

different age.

Fig. 7: Danish Tumbler ‘Grey Stipper’ and Danish

Tumblers ‘Brown Stipper’ from the author’s loft

Isabell - Dominant Opal

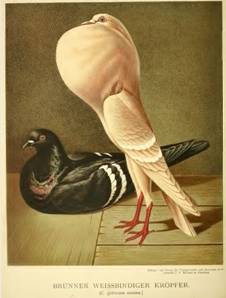

The puzzle of Isabell in the

colouring of the Brünner and Saxon Pouter with an ideally

cream-white ground colour, on which white bars were still visible,

has occupied genetically interested breeders for more than a

century. Mehlvin Ziehl had reported on his experiments and findings

in the American Pigeon Journal in the 1970s. Essential for Isabell

was, among other things, the factor Dominant Opal. With their

genetically less complex light blue relatives, they have the

white-yellow set-off wing bars or checks in common. The analysis was

complicated by the fact that homozygous Dominant Opals in are lethal

in both sexes. Once they emerged, they were white-grey and lived

only a few weeks or month. Today we know that they are best bred

with complementary colours. This also holds for other colorations

with this gene.

Fig. 8: Brünner Pouter Isabell at G. Prütz,

Illustrirtes Mustertaubenbuch, Hamburg o.J. (1885), Dominant Opal

Check from the author’s loft

Silver (Lavender) – Milky

The term silver was already

used in old literature for diluted blues. In Holland they wrote of

blue-silver. These terms are still used in breeding circles today.

At Lahore the silver-greys were already called silver (Lavalle and

Lietze 1905, Schachtzabel 1910) before W.F. Hollander had found out

that such a colouration can also be obtained by the hereditary

factor Milky in interaction with the colour spread factor. "The

reason for this foolish name ꟾmilkyꟾ was that the colour looked like

a blue pigeon that had been soaked with in milk" (Hollander 1983, p.

61). A blue pigeon dipped in milk! Blue powder was the name for a

while. With 'Spread Milky' the analogy to the milk pot seems

far-fetched. In addition to these lavenders, there are heterozygous

cocks for genetically ash-red/black ground colouring, showing the

bluish hue of the flowers of some sorts of lavender plants.

Fig. 9: Indian Fantail milky bar, Lahore Silver

(Lavender in the USA, genetically milky plus Spread at black base

colour, at the right lavender Pomeranian Eye Crested Highflyer

(heterozygous ash red/black plus Spread)

Rubella and Spread Rubella - Rubellan

The hereditary factor

Rubellan was discovered by Dr. Gerhard Knopf in racing pigeons. Some

of his pigeons resembled bar and check indigo. Somewhat more

distantly they resembled bar and check recessive opal and also

reduced coloureds with these patterns. However, the inheritance was

different from indigo and recessive opal. It corresponded to that of

Reduced. Compared to Rubella, the patterns were more intense. Later

it turned out that the factors are alleles. In the colouring of the

patterns, the discoverer of the novelty saw a similarity with the

reddish mineral Rubellan. The reddish flower colour of the Rubella

plant was not meant. After crosses with black, lighter and darker

silver-grey spread rubellan are produced in pure-bred rubellan cocks

and hemizygous females. Strikingly similar to the Spread Reduced,

Spread Recessive Opal and also Spread Platinum. But at best little

external connection to the namesake Rubellan.

Fig. 10: Rubella bar (young cock) and

Spread-Rubella hen from the author’s loft.

Andalusian - Indigo

The naming of Andalusians

follows a tortuous path. The hereditary factor 'indigo', on which

the colouration is based, was not discovered in Spain or in Spanish

pigeon breeds. Wendell M. Levi found and named 'Indigo' in the USA

in the 1940s after crossing farm pigeons with racing homers. From

white Carneau and blue racing homers there were some birds with a

bluish, indigo-coloured rump. From this derived the name for the

hereditary factor, indigo with the symbol In. When Spread was added

by mating with blacks, Spread Indigo was created. As W.F. Hollander

reported as a contemporary witness, Wendel M. Levi saw in it a

similarity to the blue colour in the chicken breed 'Andalusian'.

After imports from Spain, this breed had become popular in England

and later also in other countries in the blue colour: 'The Blue

Andalusian'. This is also written as title on the cover of a

monograph about the breed, which was published in the 2nd edition

under the pseudonym 'Silver Dun' in London in 1897. Blue in colour,

the region Andalusia as origin. In the pigeons it becomes 'coloured

like the chickens coming from Andalusia'. Like Rubellan, Indigo is

an original racing pigeon colour, which only was identified late in

pure-bred homer strains.

Fig. 11: Indigo check Racing Homer (heterozygous

Indigo with check pattern and black base color from the author’s

former racing strain); German Double-Crested Trumpeter Andalusian

(heterozygous Indigo plus Spread at black base colour), Andalusian

chicken colour, Source: Anonymous ‚Silver Dun‘, The Blue Andalusian,

2nd. ed. London 1897.

Conclusion

When considering the

designations of colour varieties of domestic pigeons, one should not

expect too strict scientific standards. They are suitable as a rough

guide. Genetic aspects could not play a major role in the naming and

classification of colourings in the beginning. Nevertheless, it is

admirable how early classifications in Bechstein 1807, Prütz 1885

and in other writings tried to bring a system into the initial

chaos. From the early naming of colourings such as Isabell (Dominant

Opal), Hyacinth (factors of the Toy-Stencil complex),

Lavender/Silver (Milky) or Almond (Stipper) one will not be able to

deduce any clues to the hereditary factors involved according to

today's knowledge or to colourings with strong genetic similarities.

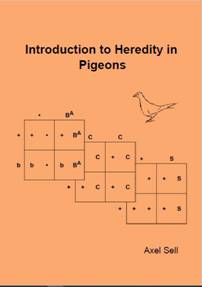

A classification of

colourings also encounters problems due to multiplicative relations.

Isabell, for example, can be listed under Dominant Opal, it is at

the same time Recessive Red and barred in the pattern systems. This

understanding of colourations as a combination of hereditary factors

is the key to understanding colour inheritance in pigeons. Currently

re-promoted as a systematic and easy-to-understand introduction with

accompanying exercises in three languages.

Fig. 12: Cover showing in symbols the mating of

two pigeons with different genetic make-up in the genetic basic

colour, the patterns checks and bars and the Spread facto. At the

right gazzi blue bronze laced on the cover ‘Colourations in the

Domestic Pigeon 2005’.

Combinations of factors will

also result in colourings that no longer have much in common with

the name of the hereditary factor. This is already evident in the

book 'Pigeon Colouring' with more than 350 different colourings

classified primarily according to hereditary factors. It is becoming

apparent that in genetic explanations, the genetic constellation is

increasingly mentioned when naming a colouration.

Literature:

Anonymous ‚Silver Dun‘, The Blue Andalusian, 2nd.

ed. London 1897.

Bechstein, Johann Matthäus, Gemeinnützige Naturgeschichte

Deutschlands nach allen drey Reichen. Ein Handbuch zur deutlichern

und vollständigern Selbstbelehrung besonders für Forstmänner,

Jugendlehrern und Oekonomen, Dritter Band, Mit Kupfern, Zweite

vermehrte und verbesserte Auflage, Leipzig 1807.

Boitard, Pierre, et Corbié, Les Pigeons de volière

et de colombier ou histoire naturelle et monographie des pigeons

domestiques, Paris 1824.

Christie, W. and Chr. Wriedt 1925, Zur Genetik der gesprenkelten

Haustaube. Zeitschrift für Induktive Abstammungs- und

Vererbungslehre 38 (1925), 271-306.

Cole, Leon J., The Blue Color in Pigeons, The Auk, Vol. 35, No. 1

(Jan., 1918), p. 105.

Eaton, J.M., A Treatise on the Art of Breeding

and Managing the Almond Tumbler, London 1851.

Fulton, R., The Illustrated Book of Pigeons,

London, Paris, New York, Melbourne 1876.

Gesner, Conrad, Vogelbuch. Darin die art/natur und eigenschafft

aller vöglen / sampt jrer waren Contrafactur / angezeigt wirt: ...

Erstlich durch doctor Conradt Geßner in Latein beschriben: neüwlich

aber durch Rudolff Heüßlin mit fleyß in das Teütsch gebracht / und

in ein kurtze ordnung gestelt, Getruckt zu Zürich bey Christoffel

Froschouwer im Jar als man zalt M.D.LVII (1557).

Hollander, W.F., Origins and Excursions in Pigeon

Genetics, Burrton, Kansas 1938.

Lavalle, A., und Lietze, M. (Hrsg.), Die Taubenrassen, Berlin 1905

Levi, W.M., The Pigeon. Sumter, South Carolina

1941, revised 1957, reprinted with minor changes and additions

1963, reprinted 1969.

Prütz, G., Illustrirtes Mustertaubenbuch, Hamburg o.J. (1885).

Schachtzabel, E., Illustriertes Prachtwerk sämtlicher Tauben-Rassen,

Würzburg o.J. (1910)

Schulz, Jürgen, Cauchois. Portrait einer französischen Rassetaube,

herausgegeben vom SV Altendorf 1987

Sell, Axel and Jana, Taubenfärbung, Oertel und Spörer.

Colourations in the Domestic Pigeon. Les Couleurs

de Pigeon, Reutlingen 2005 (with summary in English and French, 176

pages).

Sell, Axel, Genetik der Taubenfärbungen, Achim 2015, 328 Seiten

(German language).

Sell, Axel, Introduction to Heredity in Pigeon,

Achim 2022 (80 pages plus 30 p. supplement exercises). Also Dutch

and French.

Sell, Axel, Pigeon Genetics. Applied Genetics in

the Domestic Pigeon, Achim 2012, 528 pages.

|